BLOG: NEWS, RECIPES AND ARTICLES

Understanding the Gut-Skin Connection: Fixing your Skin From The Inside Out

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by bacteria. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.”

Integrative dermatology is a relatively new field that combines conventional dermatology with functional medicine principals to diagnose and treat skin conditions. It takes a holistic approach to skincare and skin conditions, recognizing that the skin's health is influenced by various factors, including nutrition, stress levels, and overall well-being. Integrative dermatology focuses on treating the whole person, rather than just the skin condition, and aims to provide comprehensive and effective treatment options for patients by addressing the underlying causes of skin issues considering the physical, biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors that affect the lives of patients with dermatological diseases.

The human body is home to ecosystems of bacteria, yeast, viruses and other organisms that inhabit different regions of our body. These ecosystems are often collectively called the microbiome. While specific species and strains of organisms vary based on location in the body, imbalances of organisms in any given site play a role in the health of the body as a whole. The microbiome is a key regulator for the immune system. Hence, imbalances (also called dysbiosis) of these organisms are associated with an altered immune response, promoting inflammation in potentially multiple areas of the body. (1) A dysbiosis can occur if there are too many “bad” species, not enough “good” species, or not enough diversity of species.

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by microbial cells. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.” Skin conditions including rosacea, acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, skin aging and others are often associated with altered gut microbiome health.

The gut and skin connection

The intestinal tract houses a diverse collection of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Many of these microorganisms are essential for metabolic and immune function. An imbalance in this microbiome can result in a breakdown of gut barrier function resulting in antigenic food proteins and bacteria components entering the body’s circulation to trigger inflammation. This inflammation can affect many organs, including the skin.

Adult Acne Vulgaris

Acne is a skin condition that occurs when your hair follicles become plugged with oil and dead skin cells. Acne can be described as whiteheads, blackheads, pimples or deep cysts. Cystic acne is linked to the health of the skin’s microbiome, in particular the balance of a bacteria called Cutibacterium acnes. In a diverse, balanced skin microbiome, this bacterium is involved in maintaining a healthy complexion. However, if there is loss of the skin microbial diversity, this bacteria can also trigger cystic acne. The microbial imbalance can lead to the activation of the immune system and a chronic inflammatory condition like acne. (2) Like in the gut, the health of the skin microbiome influences the release of chemicals triggering inflammation. Optimizing both the gut microbiome and skin microbiome are important stratagies to resolve acne by controlling inflammation both at the skin level and whole body level.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a common, chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes flushing, visible blood vessels and small, pus-filled bumps on the face. The exact cause of rosacea is debated and likely related to multiple factors. Like acne, the skin microbiome and its associated inflammatory effects plays a role in rosacea's etiology. There are also numerous studies connecting rosacea to gastrointestinal disorders including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infection and small bowel bacterial overgrowth.(3) Conventional treatment of rosacea often involves managing symptoms. Identifying and addressing potential associated gut-related illnesses is an effective tool to help support rosacea management.

Eczema

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is a chronic condition that makes skin red and itchy. It is common in children but can occur at any age. Atopic dermatitis tends to flare periodically and is often associated with asthma or allergies. Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory skin disease affecting 7% of adults and 15% of children.(1)

Studies have shown that atopic dermatitis is associated with lower gut microbiome diversity, lower levels of beneficial species, such as Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia, and Bifidobacterium in the gut, and higher amounts of harmful bacteria species including Staphylococcus aureus on the skin.(1) The intestinal microbiome modulates the body’s immune system and inflammatory responses and thus may play a role in the development of eczema and its treatment. Targeted probiotics can play a role in prevention and treatment of this disease.(4)

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory, autoimmune skin disease that causes a rash with itchy, scaly patches, most commonly on the knees, elbows, trunk and scalp. The illness is associated with an intimate interplay between genetic susceptibility, lifestyle, and environment. People with psoriasis have an increased risk to develop intestinal immune disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis and celiac disease.(1) A growing body of evidence highlights that intestinal dysbiosis is associated with the development of psoriasis.(5) One study showed that malabsorption of nutrients in the gut was more prevalent among patients with psoriasis. Celiac disease, bacterial overgrowth, parasitic infestations and eosinophilic gastroenteritis could be possible causes of malabsorption in these patients.(6) Addressing associated gut conditions may play a role in management of symptoms.

Skin Aging

Skin aging is associated with multiple degenerative processes including oxidation and inflammation. Multiple factors including diet, UV exposure, and environment play a role in the regulation of the aging process. New research shows that healthier diets are linked to fewer signs of skin aging.(7) Additionally, oral probiotics may play a role in regulating skin aging through influences on the gut-skin axis. In a study published in 2015, the oral probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 was shown to improve skin hydration, skin elasticity and UV related skin changes.(8)

Skin Care may need to Start with Gut Care

Optimizing the gut microbiome has a role in addressing skin disorders. The following strategies can improve the microbiome:

Eat better. The microbiome is influence by the food we eat. Beneficial bacteria thrive on fiber that comes from eating a variety of vegetables regularly. The growth of unfavorable bacteria is influenced by sugar, saturated fats and a lack of fiber/vegetables in the diet. To optimize your microbiome, avoid refined sugar and saturated fats like those found in sodas, breakfast cereals, candies, cakes, red meat (limit to 1 or 2 servings a week to prevent overconsumption) and what is commonly referred to as “junk food”.

Use antibiotics wisely. Antibiotic treatment is necessary from time to time. However antibiotics can significantly lower microbiome diversity and the quantity of beneficial bacteria.(9) When prescribed an antibiotic, ask your health care provider if it is truly necessary. Speak with your provider about using prebiotics and probiotics to support the microbiome after the antibiotic use.

Repair the gut flora. In addition to a fiber-rich diet, probiotics may play a role in optimizing gut function. Probiotic science is in its infancy, but there is research suggesting that certain strains may benefit certain medical conditions. Speak with your health care provider for probiotic recommendations that may best suit your medical needs.

Identify other ways to care for your digestive system, such as repairing the wall of the small intestine which may have been irritated by a poor diet, poor digestion, medications or stress. Identifying food sensitivities, restoring nutritional deficiencies and eating adequate nutrients to support healing are important.

Many of the interventions above can be easily implemented without need for laboratory tests. There are no specific gastrointestinal lab markers that are known to directly cause skin issues. However, assessments of the GI system may reveal abnormalities indirectly impacting skin health. Relish Health relies on multiple tools such as stool microbiome testing, breath tests and food sensitivity tests to understand the health of the gut-skin axis and develop targeted interventions to address gut and skin conditions.

A PRIMER ON HISTAMINE INTOLERANCE

TESTING, TESTING... WHICH ONES MIGHT BE RIGHT FOR YOU?

References:

De Pessemier B, Grine L, Debaere M, Maes A, Paetzold B, Callewaert C. Gut–Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions Microorganisms. 2021 Feb; 9(2): 353. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9020353

Dréno B,. Pécastaings S, Corvec S, Veraldi S, Khammari S, Roques C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018 Jun;32 Suppl 2:5-14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15043.

Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K, Seminario-Vidal L. Rosacea and the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther. 2021 Feb;11(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00460-1.Epub 2020 Nov 10.

Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Cuello-Garcia C, et. al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): Probiotics World Allergy Organ J. 2015; 8(1): 4. Published online 2015 Jan 27. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2

Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, Knot A, Waskiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Olszewską M, Rudnicka L. Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis: An Updated Review. Pathogens. 2020 Jun; 9(6): 463. Published online 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060463

Ojetti V, De Simone C, Sanchez J, Capizzi R, Migneco A, Guerriero C, Cazzato A, Gasbarrini G, Pierluigi A, Gasbarrini A. Malabsorption in psoriatic patients: cause or consequence? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006 Nov;41(11):1267-71.

doi: 10.1080/00365520600633529.

Katta R, Sanchez A, Tantry E. An Anti-Wrinkle Diet: Nutritional Strategies to Combat Oxidation, Inflammation and Glycation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2020 Mar;25(2):3-7.

Lee, D. E. et al. (2015) “Clinical Evidence of Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 on Skin Aging: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study,” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1509.09021

Ramirez J. Guarner F, Fernandez, L, Maruy A, Sdepanian V, Cohen H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 24 November 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.572912

Stubbe C. The Gut Microbiome in Dermatology. Anti-aging Medical News. Spring 2022. p76-80.

Is a fiber supplement right for you?

Fiber is a type of complex carbohydrate that the human body cannot digest. Instead of breaking down into sugar molecules called glucose, it instead passes through the body undigested. Fiber helps regulate the body’s use of sugars, helps feed and support the beneficial bacteria in the large intestine and helping to keep hunger and blood sugar in check.

Learn more about the benefits of fiber and where to source fiber from foods and/or supplements.

Fiber is a type of complex carbohydrate that the human body cannot digest. Instead of breaking down into sugar molecules called glucose, it instead passes through the body undigested. Fiber helps regulate the body’s use of sugars, helps feed and support the beneficial bacteria in the large intestine and helping to keep hunger and blood sugar in check.

The Food and Nutrition Board of the US Institute of Medicine recommends a total daily fiber intake of 38 g/day for men and 25 g/day for women. However, the average American consumes only about 17 g/day of dietary fiber, and dietary fiber intake might be closer to 10 g/day in those following a low-carbohydrate diet.

Types of Fiber

Fiber comes in two varieties, both are beneficial to health:

Soluble fiber, dissolves in water and includes plant pectin and gums. As soluble fiber dissolves, it creates a gel that may improve digestion. Foods with soluble fiber include oatmeal, chia seeds, nuts, beans, lentils, apples and blueberries.

Insoluble fiber, which does not dissolve in water, can help food move through your digestive system by bulking up bowel movements, promoting regularity and helping prevent constipation. Foods with insoluble fibers include whole wheat products (especially wheat bran), quinoa, brown rice, legumes, leafy greens, nuts, seeds and fruits like pears and apples. Many foods have both soluble and insoluble fibers.

What are the benefits of fiber?

Soluble fiber

Lowering cholesterol: Soluble fiber prevents some dietary cholesterol from being broken down and digested. Over time, soluble fiber can help lower cholesterol levels in the blood. Aim for five to 10 grams or more of soluble fiber a day for cholesterol lowering benefits. β-glucan (found in oat bran), raw guar gum, and psyllium are the types of fiber shown to lower cholesterol.

Stabilizing blood sugar (glucose) levels: Soluble fiber slows down the digestion rate of other nutrients including carbohydrates. This means meals containing soluble fiber are less likely to cause sharp spikes in blood sugar levels.

Lowering blood pressure: A 2018 meta-analysis of 22 randomized control trials found an overall reduction in blood pressure in people using fiber supplements or diets enriched with soluble fiber. Further analyses showed that psyllium in particular could reduce systolic blood pressure.

Reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease: By lowering cholesterol levels, stabilizing blood sugars, lowering blood pressure, and decreasing fat absorption, regularly eating soluble fiber may reduce the risk of heart disease and circulatory conditions.

Feeding healthy gut bacteria: Some soluble fiber-rich foods benefit our microbiome. They act like fertilizers that stimulate the growth of healthy bacteria in the gut.

Insoluble fiber

Preventing constipation: As an indigestible material, insoluble fiber moves through the gastrointestinal tract absorbing fluid and sticking to other byproducts of digestion that are ready to be formed into stool. Insoluble fiber speeds up the movement and processing of waste, helping the body optimize normal elimination and reduce constipation.

Lowering the risk of diverticular disease and cancer: By preventing constipation and intestinal blockages, insoluble fiber helps reduce the risk of developing small folds and hemorrhoids in the colon. It may also reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.

Both Soluble and insoluble fiber

Feeling satiated or full longer after meals: Soluble fiber slows down how quickly foods are digested, meaning most people feel full longer after fiber-rich meals. Insoluble fiber physically fills up space in the stomach and intestines, furthering the sensation of being full. These properties can help people manage their weight.

Helping lower disease risk: Due to fiber’s many health benefits, a high-fiber diet is associated with a lower risk of many diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and others.

Where to find fiber naturally

Good food sources of fiber include whole grains, whole fruit and vegetables, legumes, nuts and seeds.

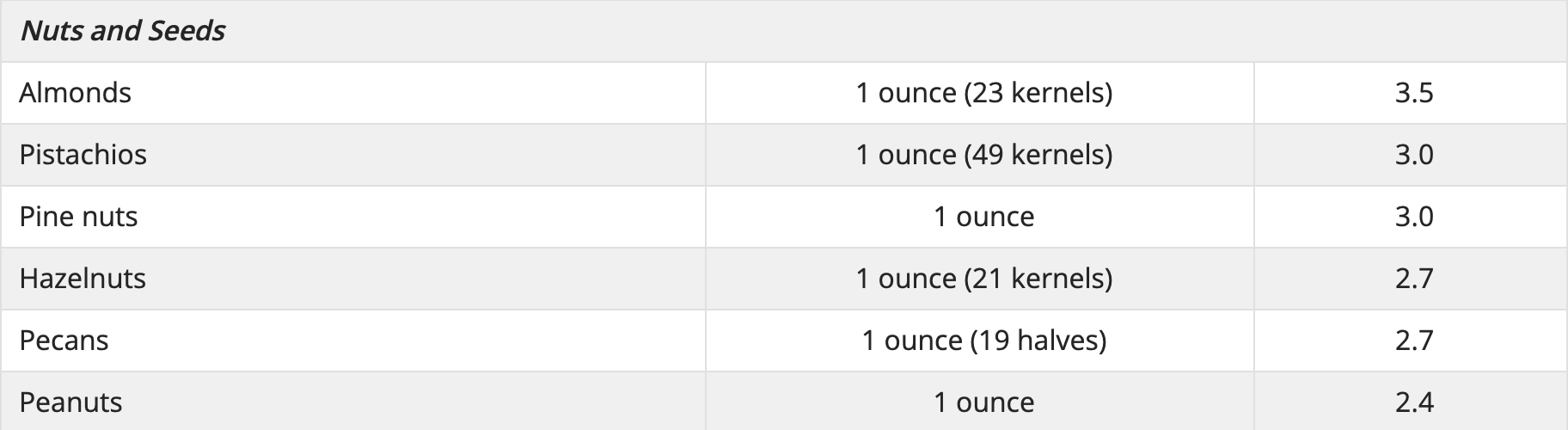

Some Food Sources of Dietary Fiber Linus Pauling Institute Oregon State University

Types of fiber supplements:

β-Glucans

β-Glucans are soluble fibers found naturally in oats, barley, mushrooms, yeast, bacteria and algae. β-Glucans extracted from oats, mushrooms, and yeast are available in a variety of nutritional supplement capsules without a prescription.

Glucomannan

Glucomannan, sometimes called konjac mannan, is classified as a soluble fiber isolated from konjac flour. Glucomannan is available as powder and in capsules, which should be taken with plenty of liquids.

Pectin

Pectins are soluble fibers most often extracted from citrus peels and apple pulp. Recipe for pectin-rich stewed apples.

Inulins and oligofructose

Inulins and oligofructose, extracted from chicory root are used as food additives. They are also classifies as prebiotics because of their ability to stimulate the growth of potentially beneficial Bifidobacteria species in the colon. Inulin is produced by many plants and is composed mainly of fructose. A number of dietary supplements and packaged “high fiber foods” containing inulins and oligofructose.

Guar gum

Raw guar gum is used as a thickener or emulsifier in many food products. Dietary supplements containing guar gum have been marketed as weight-loss aids, but there is no evidence of their efficacy. Unlike guar gum, partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG, Sunfiber) has no effect on serum cholesterol or blood sugar levels. However, PHGG is a low FODMAP fiber and is less likely to trigger bloating or cramping in people with irritable bowel syndrome.

Psyllium

Psyllium, a soluble, gel-forming fiber isolated from psyllium seed husks, is available without a prescription in laxatives, ready-to-eat cereal, and dietary supplements. Psyllium (the main component of Metamucil) is proven to be effective to lower serum cholesterol and improve blood sugar balance. Because it also normalizes stool form, psyllium is the only fiber recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology to treat chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome.

Wheat Dextan

Wheat dextrin (Benefiber) is a form of wheat starch. The manufacturers considers it gluten-free because it contains less than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten. However, people with gluten intolerance or celiac disease should not use Benefiber unless directed by a doctor.

Polycarbofil

Polycarbofil (Fibercon) is a synthetic polymer that is used as stool stabilizer to treat constipation, diarrhea and abdominal discomfort.

Methylcellulose

Methylcellulose (Citrucel) found in fiber supplements is a synthetic product derived from cellulose. Methylcellulose is not broken down and digested in the intestines, but rather absorbs water and becomes gel-like to add bulk to the stool. Because methylcellulose does not ferment, it may cause less gas and bloating in some individuals.

Polydextrose

Polydextrose is a complex carbohydrate made from glucose. It is made in a lab and is not digested by the body. Polydextrose is often used as a prebiotic to support the growth of beneficial bacteria in the microbiome.

**Do not take fiber supplements within 1 hour of other medications or some supplements including calcium, iron, and zinc. Fiber can interfere with absorption.

Understanding the Gut-Skin Connection: Fixing your Gut May Fix Your Skin

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by bacteria. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.”

The human body is home to ecosystems of bacteria, yeast, viruses and other organisms that inhabit different regions of our body. These ecosystems are often collectively called the microbiome. While specific species and strains of organisms vary based on location in the body, imbalances of organisms in any given site play a role in the health of the body as a whole. The microbiome is a key regulator for the immune system. Hence, imbalances (also called dysbiosis) of these organisms are associated with an altered immune response, promoting inflammation in potentially multiple areas of the body. (1) A dysbiosis can occur if there are too many “bad” species, not enough “good” species, or not enough diversity of species.

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by microbial cells. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.” Skin conditions including rosacea, acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, skin aging and others are often associated with altered gut microbiome health.

The gut and skin connection

The intestinal tract houses a diverse collection of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Many of these microorganisms are essential for metabolic and immune function. An imbalance in this microbiome can result in a breakdown of gut barrier function resulting in antigenic food proteins and bacteria components entering the body’s circulation to trigger inflammation. This inflammation can affect many organs, including the skin.

Adult Acne Vulgaris

Acne is a skin condition that occurs when your hair follicles become plugged with oil and dead skin cells. Acne can be described as whiteheads, blackheads, pimples or deep cysts. Cystic acne is linked to the health of the skin’s microbiome, in particular the balance of a bacteria called Cutibacterium acnes. In a diverse, balanced skin microbiome, this bacterium is involved in maintaining a healthy complexion. However, if there is loss of the skin microbial diversity, this bacteria can also trigger cystic acne. The microbial imbalance can lead to the activation of the immune system and a chronic inflammatory condition like acne. (2) Like in the gut, the health of the skin microbiome influences the release of chemicals triggering inflammation. Optimizing both the gut microbiome and skin microbiome are important stratagies to resolve acne by controlling inflammation both at the skin level and whole body level.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a common, chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes flushing, visible blood vessels and small, pus-filled bumps on the face. The exact cause of rosacea is debated and likely related to multiple factors. Like acne, the skin microbiome and its associated inflammatory effects plays a role in rosacea's etiology. There are also numerous studies connecting rosacea to gastrointestinal disorders including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infection and small bowel bacterial overgrowth.(3) Conventional treatment of rosacea often involves managing symptoms. Identifying and addressing potential associated gut-related illnesses is an effective tool to help support rosacea management.

Eczema

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is a chronic condition that makes skin red and itchy. It is common in children but can occur at any age. Atopic dermatitis tends to flare periodically and is often associated with asthma or allergies. Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory skin disease affecting 7% of adults and 15% of children.(1)

Studies have shown that atopic dermatitis is associated with lower gut microbiome diversity, lower levels of beneficial species, such as Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia, and Bifidobacterium in the gut, and higher amounts of harmful bacteria species including Staphylococcus aureus on the skin.(1) The intestinal microbiome modulates the body’s immune system and inflammatory responses and thus may play a role in the development of eczema and its treatment. Targeted probiotics can play a role in prevention and treatment of this disease.(4)

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory, autoimmune skin disease that causes a rash with itchy, scaly patches, most commonly on the knees, elbows, trunk and scalp. The illness is associated with an intimate interplay between genetic susceptibility, lifestyle, and environment. People with psoriasis have an increased risk to develop intestinal immune disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis and celiac disease.(1) A growing body of evidence highlights that intestinal dysbiosis is associated with the development of psoriasis.(5) One study showed that malabsorption of nutrients in the gut was more prevalent among patients with psoriasis. Celiac disease, bacterial overgrowth, parasitic infestations and eosinophilic gastroenteritis could be possible causes of malabsorption in these patients.(6) Addressing associated gut conditions may play a role in management of symptoms.

Skin Aging

Skin aging is associated with multiple degenerative processes including oxidation and inflammation. Multiple factors including diet, UV exposure, and environment play a role in the regulation of the aging process. New research shows that healthier diets are linked to fewer signs of skin aging.(7) Additionally, oral probiotics may play a role in regulating skin aging through influences on the gut-skin axis. In a study published in 2015, the oral probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 was shown to improve skin hydration, skin elasticity and UV related skin changes.(8)

Skin Care may need to Start with Gut Care

Optimizing the gut microbiome has a role in addressing skin disorders. The following strategies can improve the microbiome:

Eat better. The microbiome is influence by the food we eat. Beneficial bacteria thrive on fiber that comes from eating a variety of vegetables regularly. The growth of unfavorable bacteria is influenced by sugar, saturated fats and a lack of fiber/vegetables in the diet. To optimize your microbiome, avoid refined sugar and saturated fats like those found in sodas, breakfast cereals, candies, cakes, red meat (limit to 1 or 2 servings a week to prevent overconsumption) and what is commonly referred to as “junk food”.

Use antibiotics wisely. Antibiotic treatment is necessary from time to time. However antibiotics can significantly lower microbiome diversity and the quantity of beneficial bacteria.(9) When prescribed an antibiotic, ask your health care provider if it is truly necessary. Speak with your provider about using prebiotics and probiotics to support the microbiome after the antibiotic use.

Repair the gut flora. In addition to a fiber-rich diet, probiotics may play a role in optimizing gut function. Probiotic science is in its infancy, but there is research suggesting that certain strains may benefit certain medical conditions. Speak with your health care provider for probiotic recommendations that may best suit your medical needs.

Identify other ways to care for your digestive system, such as repairing the wall of the small intestine which may have been irritated by a poor diet, poor digestion, medications or stress. Identifying food sensitivities, restoring nutritional deficiencies and eating adequate nutrients to support healing are important.

Many of the interventions above can be easily implemented without need for laboratory tests. There are no specific gastrointestinal lab markers that are known to directly cause skin issues. However, assessments of the GI system may reveal abnormalities indirectly impacting skin health. Relish Health relies on multiple tools such as stool microbiome testing, breath tests and food sensitivity tests to understand the health of the gut-skin axis and develop targeted interventions to address gut and skin conditions.

TESTING, TESTING... WHICH ONES MIGHT BE RIGHT FOR YOU?

References:

De Pessemier B, Grine L, Debaere M, Maes A, Paetzold B, Callewaert C. Gut–Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions Microorganisms. 2021 Feb; 9(2): 353. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9020353

Dréno B,. Pécastaings S, Corvec S, Veraldi S, Khammari S, Roques C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018 Jun;32 Suppl 2:5-14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15043.

Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K, Seminario-Vidal L. Rosacea and the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther. 2021 Feb;11(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00460-1.Epub 2020 Nov 10.

Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Cuello-Garcia C, et. al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): Probiotics World Allergy Organ J. 2015; 8(1): 4. Published online 2015 Jan 27. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2

Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, Knot A, Waskiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Olszewską M, Rudnicka L. Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis: An Updated Review. Pathogens. 2020 Jun; 9(6): 463. Published online 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060463

Ojetti V, De Simone C, Sanchez J, Capizzi R, Migneco A, Guerriero C, Cazzato A, Gasbarrini G, Pierluigi A, Gasbarrini A. Malabsorption in psoriatic patients: cause or consequence? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006 Nov;41(11):1267-71.

doi: 10.1080/00365520600633529.

Katta R, Sanchez A, Tantry E. An Anti-Wrinkle Diet: Nutritional Strategies to Combat Oxidation, Inflammation and Glycation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2020 Mar;25(2):3-7.

Lee, D. E. et al. (2015) “Clinical Evidence of Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 on Skin Aging: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study,” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1509.09021

Ramirez J. Guarner F, Fernandez, L, Maruy A, Sdepanian V, Cohen H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 24 November 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.572912

Stubbe C. The Gut Microbiome in Dermatology. Anti-aging Medical News. Spring 2022. p76-80.