BLOG: NEWS, RECIPES AND ARTICLES

The Intricate Dance of Gut Microbes and Hormones: A Key to Women's Health

Our bodies are home to trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the microbiome. Recent research has shed light on the fascinating relationship between the gut microbiome and our hormonal systems, particularly in women. This interplay has far-reaching implications for various aspects of health, from reproductive issues to metabolic disorders.

Our bodies are home to trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the microbiome. Recent research has shed light on the fascinating relationship between the gut microbiome and our hormonal systems, particularly in women. This interplay has far-reaching implications for various aspects of health, from reproductive issues to metabolic disorders.

The Gut Microbiome: More Than Just Digestion

The gut microbiome is a complex ecosystem of bacteria residing in our intestines. Far from being passive inhabitants, these microbes play crucial roles in our overall health. They influence not only digestion but also our immune system, metabolism, and even our mood. Remarkably, the gut microbiome is now considered an endocrine organ in its own right, capable of producing and regulating hormones.

Estrogen and the Gut: A Two-Way Street

One of the most significant interactions occurs between gut bacteria and estrogen, a primary female sex hormone. This relationship is so important that researchers have coined the term "estrobolome" to describe the collection of gut bacteria capable of metabolizing estrogen. Here's how it works:

Some gut bacteria produce an enzyme called β-glucuronidase, which helps activate estrogen in the body.

An imbalance in these bacteria can lead to either too much or too little active estrogen, potentially contributing to conditions like endometriosis, PCOS, and certain cancers.

Conversely, estrogen itself can influence the composition of the gut microbiome, creating a feedback loop.

Androgens and Gut Health

While often considered male hormones, androgens like testosterone also play crucial roles in women's health. Elevated androgen levels, a condition known as hyperandrogenaemia, are common in PCOS and can affect the gut microbiome. Studies have shown that:

High androgen levels correlate with changes in specific gut bacteria populations.

These alterations may contribute to the metabolic issues often seen in PCOS, such as insulin resistance and obesity.

Implications for Women's Health

Understanding these intricate relationships opens up new avenues for addressing women's health issues:

Personalized Medicine: By analyzing an individual's gut microbiome, healthcare providers might better predict and treat hormonal imbalances.

Novel Treatments: Probiotics or targeted dietary interventions could potentially help manage conditions like PCOS by modulating the gut microbiome.

Preventive Care: Maintaining a healthy gut microbiome through diet and lifestyle choices may help prevent hormonal issues before they arise.

Fertility Support: For women struggling with fertility, addressing gut health could be a complementary approach to traditional treatments.

Conclusion

The discovery of the gut microbiome's role in hormonal health is revolutionizing our understanding of women's health. It underscores the importance of a holistic approach to healthcare, considering the interconnectedness of various bodily systems. While research in this field is still evolving, it's clear that nurturing our gut health through a balanced diet, regular exercise, and stress management could have far-reaching benefits for hormonal balance and overall well-being. As we continue to unravel the mysteries of the gut microbiome, we may find new keys to addressing long-standing health challenges, offering hope for more effective and personalized treatments in women's health.

Steps to Prepare You for Bioidentical Hormones

References:

Qi X, Yun C, Pang Y, Qiao J. The impact of the gut microbiota on the reproductive and metabolic endocrine system. Gut Microbes. 2021 Jan-Dec;13(1):1-21. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1894070. PMID: 33722164; PMCID: PMC7971312.

He S, Li H, Yu Z, Zhang F, Liang S, Liu H, Chen H, Lü M. The Gut Microbiome and Sex Hormone-Related Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2021 Sep 28;12:711137. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.711137. PMID: 34650525; PMCID: PMC8506209.

Understanding the Gut-Skin Connection: Fixing your Skin From The Inside Out

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by bacteria. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.”

Integrative dermatology is a relatively new field that combines conventional dermatology with functional medicine principals to diagnose and treat skin conditions. It takes a holistic approach to skincare and skin conditions, recognizing that the skin's health is influenced by various factors, including nutrition, stress levels, and overall well-being. Integrative dermatology focuses on treating the whole person, rather than just the skin condition, and aims to provide comprehensive and effective treatment options for patients by addressing the underlying causes of skin issues considering the physical, biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors that affect the lives of patients with dermatological diseases.

The human body is home to ecosystems of bacteria, yeast, viruses and other organisms that inhabit different regions of our body. These ecosystems are often collectively called the microbiome. While specific species and strains of organisms vary based on location in the body, imbalances of organisms in any given site play a role in the health of the body as a whole. The microbiome is a key regulator for the immune system. Hence, imbalances (also called dysbiosis) of these organisms are associated with an altered immune response, promoting inflammation in potentially multiple areas of the body. (1) A dysbiosis can occur if there are too many “bad” species, not enough “good” species, or not enough diversity of species.

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by microbial cells. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.” Skin conditions including rosacea, acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, skin aging and others are often associated with altered gut microbiome health.

The gut and skin connection

The intestinal tract houses a diverse collection of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Many of these microorganisms are essential for metabolic and immune function. An imbalance in this microbiome can result in a breakdown of gut barrier function resulting in antigenic food proteins and bacteria components entering the body’s circulation to trigger inflammation. This inflammation can affect many organs, including the skin.

Adult Acne Vulgaris

Acne is a skin condition that occurs when your hair follicles become plugged with oil and dead skin cells. Acne can be described as whiteheads, blackheads, pimples or deep cysts. Cystic acne is linked to the health of the skin’s microbiome, in particular the balance of a bacteria called Cutibacterium acnes. In a diverse, balanced skin microbiome, this bacterium is involved in maintaining a healthy complexion. However, if there is loss of the skin microbial diversity, this bacteria can also trigger cystic acne. The microbial imbalance can lead to the activation of the immune system and a chronic inflammatory condition like acne. (2) Like in the gut, the health of the skin microbiome influences the release of chemicals triggering inflammation. Optimizing both the gut microbiome and skin microbiome are important stratagies to resolve acne by controlling inflammation both at the skin level and whole body level.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a common, chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes flushing, visible blood vessels and small, pus-filled bumps on the face. The exact cause of rosacea is debated and likely related to multiple factors. Like acne, the skin microbiome and its associated inflammatory effects plays a role in rosacea's etiology. There are also numerous studies connecting rosacea to gastrointestinal disorders including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infection and small bowel bacterial overgrowth.(3) Conventional treatment of rosacea often involves managing symptoms. Identifying and addressing potential associated gut-related illnesses is an effective tool to help support rosacea management.

Eczema

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is a chronic condition that makes skin red and itchy. It is common in children but can occur at any age. Atopic dermatitis tends to flare periodically and is often associated with asthma or allergies. Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory skin disease affecting 7% of adults and 15% of children.(1)

Studies have shown that atopic dermatitis is associated with lower gut microbiome diversity, lower levels of beneficial species, such as Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia, and Bifidobacterium in the gut, and higher amounts of harmful bacteria species including Staphylococcus aureus on the skin.(1) The intestinal microbiome modulates the body’s immune system and inflammatory responses and thus may play a role in the development of eczema and its treatment. Targeted probiotics can play a role in prevention and treatment of this disease.(4)

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory, autoimmune skin disease that causes a rash with itchy, scaly patches, most commonly on the knees, elbows, trunk and scalp. The illness is associated with an intimate interplay between genetic susceptibility, lifestyle, and environment. People with psoriasis have an increased risk to develop intestinal immune disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis and celiac disease.(1) A growing body of evidence highlights that intestinal dysbiosis is associated with the development of psoriasis.(5) One study showed that malabsorption of nutrients in the gut was more prevalent among patients with psoriasis. Celiac disease, bacterial overgrowth, parasitic infestations and eosinophilic gastroenteritis could be possible causes of malabsorption in these patients.(6) Addressing associated gut conditions may play a role in management of symptoms.

Skin Aging

Skin aging is associated with multiple degenerative processes including oxidation and inflammation. Multiple factors including diet, UV exposure, and environment play a role in the regulation of the aging process. New research shows that healthier diets are linked to fewer signs of skin aging.(7) Additionally, oral probiotics may play a role in regulating skin aging through influences on the gut-skin axis. In a study published in 2015, the oral probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 was shown to improve skin hydration, skin elasticity and UV related skin changes.(8)

Skin Care may need to Start with Gut Care

Optimizing the gut microbiome has a role in addressing skin disorders. The following strategies can improve the microbiome:

Eat better. The microbiome is influence by the food we eat. Beneficial bacteria thrive on fiber that comes from eating a variety of vegetables regularly. The growth of unfavorable bacteria is influenced by sugar, saturated fats and a lack of fiber/vegetables in the diet. To optimize your microbiome, avoid refined sugar and saturated fats like those found in sodas, breakfast cereals, candies, cakes, red meat (limit to 1 or 2 servings a week to prevent overconsumption) and what is commonly referred to as “junk food”.

Use antibiotics wisely. Antibiotic treatment is necessary from time to time. However antibiotics can significantly lower microbiome diversity and the quantity of beneficial bacteria.(9) When prescribed an antibiotic, ask your health care provider if it is truly necessary. Speak with your provider about using prebiotics and probiotics to support the microbiome after the antibiotic use.

Repair the gut flora. In addition to a fiber-rich diet, probiotics may play a role in optimizing gut function. Probiotic science is in its infancy, but there is research suggesting that certain strains may benefit certain medical conditions. Speak with your health care provider for probiotic recommendations that may best suit your medical needs.

Identify other ways to care for your digestive system, such as repairing the wall of the small intestine which may have been irritated by a poor diet, poor digestion, medications or stress. Identifying food sensitivities, restoring nutritional deficiencies and eating adequate nutrients to support healing are important.

Many of the interventions above can be easily implemented without need for laboratory tests. There are no specific gastrointestinal lab markers that are known to directly cause skin issues. However, assessments of the GI system may reveal abnormalities indirectly impacting skin health. Relish Health relies on multiple tools such as stool microbiome testing, breath tests and food sensitivity tests to understand the health of the gut-skin axis and develop targeted interventions to address gut and skin conditions.

A PRIMER ON HISTAMINE INTOLERANCE

TESTING, TESTING... WHICH ONES MIGHT BE RIGHT FOR YOU?

References:

De Pessemier B, Grine L, Debaere M, Maes A, Paetzold B, Callewaert C. Gut–Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions Microorganisms. 2021 Feb; 9(2): 353. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9020353

Dréno B,. Pécastaings S, Corvec S, Veraldi S, Khammari S, Roques C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018 Jun;32 Suppl 2:5-14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15043.

Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K, Seminario-Vidal L. Rosacea and the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther. 2021 Feb;11(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00460-1.Epub 2020 Nov 10.

Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Cuello-Garcia C, et. al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): Probiotics World Allergy Organ J. 2015; 8(1): 4. Published online 2015 Jan 27. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2

Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, Knot A, Waskiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Olszewską M, Rudnicka L. Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis: An Updated Review. Pathogens. 2020 Jun; 9(6): 463. Published online 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060463

Ojetti V, De Simone C, Sanchez J, Capizzi R, Migneco A, Guerriero C, Cazzato A, Gasbarrini G, Pierluigi A, Gasbarrini A. Malabsorption in psoriatic patients: cause or consequence? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006 Nov;41(11):1267-71.

doi: 10.1080/00365520600633529.

Katta R, Sanchez A, Tantry E. An Anti-Wrinkle Diet: Nutritional Strategies to Combat Oxidation, Inflammation and Glycation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2020 Mar;25(2):3-7.

Lee, D. E. et al. (2015) “Clinical Evidence of Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 on Skin Aging: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study,” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1509.09021

Ramirez J. Guarner F, Fernandez, L, Maruy A, Sdepanian V, Cohen H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 24 November 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.572912

Stubbe C. The Gut Microbiome in Dermatology. Anti-aging Medical News. Spring 2022. p76-80.

Is a fiber supplement right for you?

Fiber is a type of complex carbohydrate that the human body cannot digest. Instead of breaking down into sugar molecules called glucose, it instead passes through the body undigested. Fiber helps regulate the body’s use of sugars, helps feed and support the beneficial bacteria in the large intestine and helping to keep hunger and blood sugar in check.

Learn more about the benefits of fiber and where to source fiber from foods and/or supplements.

Fiber is a type of complex carbohydrate that the human body cannot digest. Instead of breaking down into sugar molecules called glucose, it instead passes through the body undigested. Fiber helps regulate the body’s use of sugars, helps feed and support the beneficial bacteria in the large intestine and helping to keep hunger and blood sugar in check.

The Food and Nutrition Board of the US Institute of Medicine recommends a total daily fiber intake of 38 g/day for men and 25 g/day for women. However, the average American consumes only about 17 g/day of dietary fiber, and dietary fiber intake might be closer to 10 g/day in those following a low-carbohydrate diet.

Types of Fiber

Fiber comes in two varieties, both are beneficial to health:

Soluble fiber, dissolves in water and includes plant pectin and gums. As soluble fiber dissolves, it creates a gel that may improve digestion. Foods with soluble fiber include oatmeal, chia seeds, nuts, beans, lentils, apples and blueberries.

Insoluble fiber, which does not dissolve in water, can help food move through your digestive system by bulking up bowel movements, promoting regularity and helping prevent constipation. Foods with insoluble fibers include whole wheat products (especially wheat bran), quinoa, brown rice, legumes, leafy greens, nuts, seeds and fruits like pears and apples. Many foods have both soluble and insoluble fibers.

What are the benefits of fiber?

Soluble fiber

Lowering cholesterol: Soluble fiber prevents some dietary cholesterol from being broken down and digested. Over time, soluble fiber can help lower cholesterol levels in the blood. Aim for five to 10 grams or more of soluble fiber a day for cholesterol lowering benefits. β-glucan (found in oat bran), raw guar gum, and psyllium are the types of fiber shown to lower cholesterol.

Stabilizing blood sugar (glucose) levels: Soluble fiber slows down the digestion rate of other nutrients including carbohydrates. This means meals containing soluble fiber are less likely to cause sharp spikes in blood sugar levels.

Lowering blood pressure: A 2018 meta-analysis of 22 randomized control trials found an overall reduction in blood pressure in people using fiber supplements or diets enriched with soluble fiber. Further analyses showed that psyllium in particular could reduce systolic blood pressure.

Reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease: By lowering cholesterol levels, stabilizing blood sugars, lowering blood pressure, and decreasing fat absorption, regularly eating soluble fiber may reduce the risk of heart disease and circulatory conditions.

Feeding healthy gut bacteria: Some soluble fiber-rich foods benefit our microbiome. They act like fertilizers that stimulate the growth of healthy bacteria in the gut.

Insoluble fiber

Preventing constipation: As an indigestible material, insoluble fiber moves through the gastrointestinal tract absorbing fluid and sticking to other byproducts of digestion that are ready to be formed into stool. Insoluble fiber speeds up the movement and processing of waste, helping the body optimize normal elimination and reduce constipation.

Lowering the risk of diverticular disease and cancer: By preventing constipation and intestinal blockages, insoluble fiber helps reduce the risk of developing small folds and hemorrhoids in the colon. It may also reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.

Both Soluble and insoluble fiber

Feeling satiated or full longer after meals: Soluble fiber slows down how quickly foods are digested, meaning most people feel full longer after fiber-rich meals. Insoluble fiber physically fills up space in the stomach and intestines, furthering the sensation of being full. These properties can help people manage their weight.

Helping lower disease risk: Due to fiber’s many health benefits, a high-fiber diet is associated with a lower risk of many diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and others.

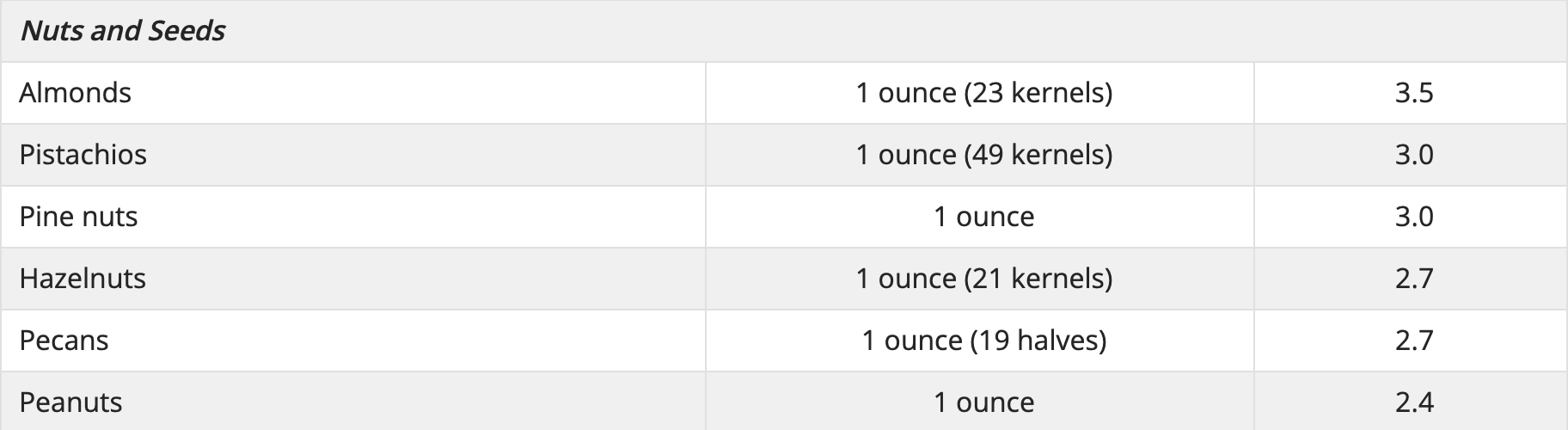

Where to find fiber naturally

Good food sources of fiber include whole grains, whole fruit and vegetables, legumes, nuts and seeds.

Some Food Sources of Dietary Fiber Linus Pauling Institute Oregon State University

Types of fiber supplements:

β-Glucans

β-Glucans are soluble fibers found naturally in oats, barley, mushrooms, yeast, bacteria and algae. β-Glucans extracted from oats, mushrooms, and yeast are available in a variety of nutritional supplement capsules without a prescription.

Glucomannan

Glucomannan, sometimes called konjac mannan, is classified as a soluble fiber isolated from konjac flour. Glucomannan is available as powder and in capsules, which should be taken with plenty of liquids.

Pectin

Pectins are soluble fibers most often extracted from citrus peels and apple pulp. Recipe for pectin-rich stewed apples.

Inulins and oligofructose

Inulins and oligofructose, extracted from chicory root are used as food additives. They are also classifies as prebiotics because of their ability to stimulate the growth of potentially beneficial Bifidobacteria species in the colon. Inulin is produced by many plants and is composed mainly of fructose. A number of dietary supplements and packaged “high fiber foods” containing inulins and oligofructose.

Guar gum

Raw guar gum is used as a thickener or emulsifier in many food products. Dietary supplements containing guar gum have been marketed as weight-loss aids, but there is no evidence of their efficacy. Unlike guar gum, partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG, Sunfiber) has no effect on serum cholesterol or blood sugar levels. However, PHGG is a low FODMAP fiber and is less likely to trigger bloating or cramping in people with irritable bowel syndrome.

Psyllium

Psyllium, a soluble, gel-forming fiber isolated from psyllium seed husks, is available without a prescription in laxatives, ready-to-eat cereal, and dietary supplements. Psyllium (the main component of Metamucil) is proven to be effective to lower serum cholesterol and improve blood sugar balance. Because it also normalizes stool form, psyllium is the only fiber recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology to treat chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome.

Wheat Dextan

Wheat dextrin (Benefiber) is a form of wheat starch. The manufacturers considers it gluten-free because it contains less than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten. However, people with gluten intolerance or celiac disease should not use Benefiber unless directed by a doctor.

Polycarbofil

Polycarbofil (Fibercon) is a synthetic polymer that is used as stool stabilizer to treat constipation, diarrhea and abdominal discomfort.

Methylcellulose

Methylcellulose (Citrucel) found in fiber supplements is a synthetic product derived from cellulose. Methylcellulose is not broken down and digested in the intestines, but rather absorbs water and becomes gel-like to add bulk to the stool. Because methylcellulose does not ferment, it may cause less gas and bloating in some individuals.

Polydextrose

Polydextrose is a complex carbohydrate made from glucose. It is made in a lab and is not digested by the body. Polydextrose is often used as a prebiotic to support the growth of beneficial bacteria in the microbiome.

**Do not take fiber supplements within 1 hour of other medications or some supplements including calcium, iron, and zinc. Fiber can interfere with absorption.

Understanding the Gut-Skin Connection: Fixing your Gut May Fix Your Skin

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by bacteria. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.”

The human body is home to ecosystems of bacteria, yeast, viruses and other organisms that inhabit different regions of our body. These ecosystems are often collectively called the microbiome. While specific species and strains of organisms vary based on location in the body, imbalances of organisms in any given site play a role in the health of the body as a whole. The microbiome is a key regulator for the immune system. Hence, imbalances (also called dysbiosis) of these organisms are associated with an altered immune response, promoting inflammation in potentially multiple areas of the body. (1) A dysbiosis can occur if there are too many “bad” species, not enough “good” species, or not enough diversity of species.

The skin is the largest and most external barrier of the body with the outer environment. It is richly perfused with immune cells and heavily colonized by microbial cells. These microbes help train the body’s immune cells and help determine overall well-being. The skin has a unique microbiome that is distinct from the gut microbiome, yet scientists are learning that there is a strong bidirectional relationship between the health of these two areas of the body. The relationship is often termed the “gut-skin axis.” Skin conditions including rosacea, acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, skin aging and others are often associated with altered gut microbiome health.

The gut and skin connection

The intestinal tract houses a diverse collection of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Many of these microorganisms are essential for metabolic and immune function. An imbalance in this microbiome can result in a breakdown of gut barrier function resulting in antigenic food proteins and bacteria components entering the body’s circulation to trigger inflammation. This inflammation can affect many organs, including the skin.

Adult Acne Vulgaris

Acne is a skin condition that occurs when your hair follicles become plugged with oil and dead skin cells. Acne can be described as whiteheads, blackheads, pimples or deep cysts. Cystic acne is linked to the health of the skin’s microbiome, in particular the balance of a bacteria called Cutibacterium acnes. In a diverse, balanced skin microbiome, this bacterium is involved in maintaining a healthy complexion. However, if there is loss of the skin microbial diversity, this bacteria can also trigger cystic acne. The microbial imbalance can lead to the activation of the immune system and a chronic inflammatory condition like acne. (2) Like in the gut, the health of the skin microbiome influences the release of chemicals triggering inflammation. Optimizing both the gut microbiome and skin microbiome are important stratagies to resolve acne by controlling inflammation both at the skin level and whole body level.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a common, chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes flushing, visible blood vessels and small, pus-filled bumps on the face. The exact cause of rosacea is debated and likely related to multiple factors. Like acne, the skin microbiome and its associated inflammatory effects plays a role in rosacea's etiology. There are also numerous studies connecting rosacea to gastrointestinal disorders including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infection and small bowel bacterial overgrowth.(3) Conventional treatment of rosacea often involves managing symptoms. Identifying and addressing potential associated gut-related illnesses is an effective tool to help support rosacea management.

Eczema

Eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is a chronic condition that makes skin red and itchy. It is common in children but can occur at any age. Atopic dermatitis tends to flare periodically and is often associated with asthma or allergies. Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory skin disease affecting 7% of adults and 15% of children.(1)

Studies have shown that atopic dermatitis is associated with lower gut microbiome diversity, lower levels of beneficial species, such as Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia, and Bifidobacterium in the gut, and higher amounts of harmful bacteria species including Staphylococcus aureus on the skin.(1) The intestinal microbiome modulates the body’s immune system and inflammatory responses and thus may play a role in the development of eczema and its treatment. Targeted probiotics can play a role in prevention and treatment of this disease.(4)

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory, autoimmune skin disease that causes a rash with itchy, scaly patches, most commonly on the knees, elbows, trunk and scalp. The illness is associated with an intimate interplay between genetic susceptibility, lifestyle, and environment. People with psoriasis have an increased risk to develop intestinal immune disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis and celiac disease.(1) A growing body of evidence highlights that intestinal dysbiosis is associated with the development of psoriasis.(5) One study showed that malabsorption of nutrients in the gut was more prevalent among patients with psoriasis. Celiac disease, bacterial overgrowth, parasitic infestations and eosinophilic gastroenteritis could be possible causes of malabsorption in these patients.(6) Addressing associated gut conditions may play a role in management of symptoms.

Skin Aging

Skin aging is associated with multiple degenerative processes including oxidation and inflammation. Multiple factors including diet, UV exposure, and environment play a role in the regulation of the aging process. New research shows that healthier diets are linked to fewer signs of skin aging.(7) Additionally, oral probiotics may play a role in regulating skin aging through influences on the gut-skin axis. In a study published in 2015, the oral probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 was shown to improve skin hydration, skin elasticity and UV related skin changes.(8)

Skin Care may need to Start with Gut Care

Optimizing the gut microbiome has a role in addressing skin disorders. The following strategies can improve the microbiome:

Eat better. The microbiome is influence by the food we eat. Beneficial bacteria thrive on fiber that comes from eating a variety of vegetables regularly. The growth of unfavorable bacteria is influenced by sugar, saturated fats and a lack of fiber/vegetables in the diet. To optimize your microbiome, avoid refined sugar and saturated fats like those found in sodas, breakfast cereals, candies, cakes, red meat (limit to 1 or 2 servings a week to prevent overconsumption) and what is commonly referred to as “junk food”.

Use antibiotics wisely. Antibiotic treatment is necessary from time to time. However antibiotics can significantly lower microbiome diversity and the quantity of beneficial bacteria.(9) When prescribed an antibiotic, ask your health care provider if it is truly necessary. Speak with your provider about using prebiotics and probiotics to support the microbiome after the antibiotic use.

Repair the gut flora. In addition to a fiber-rich diet, probiotics may play a role in optimizing gut function. Probiotic science is in its infancy, but there is research suggesting that certain strains may benefit certain medical conditions. Speak with your health care provider for probiotic recommendations that may best suit your medical needs.

Identify other ways to care for your digestive system, such as repairing the wall of the small intestine which may have been irritated by a poor diet, poor digestion, medications or stress. Identifying food sensitivities, restoring nutritional deficiencies and eating adequate nutrients to support healing are important.

Many of the interventions above can be easily implemented without need for laboratory tests. There are no specific gastrointestinal lab markers that are known to directly cause skin issues. However, assessments of the GI system may reveal abnormalities indirectly impacting skin health. Relish Health relies on multiple tools such as stool microbiome testing, breath tests and food sensitivity tests to understand the health of the gut-skin axis and develop targeted interventions to address gut and skin conditions.

TESTING, TESTING... WHICH ONES MIGHT BE RIGHT FOR YOU?

References:

De Pessemier B, Grine L, Debaere M, Maes A, Paetzold B, Callewaert C. Gut–Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions Microorganisms. 2021 Feb; 9(2): 353. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9020353

Dréno B,. Pécastaings S, Corvec S, Veraldi S, Khammari S, Roques C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018 Jun;32 Suppl 2:5-14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15043.

Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K, Seminario-Vidal L. Rosacea and the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther. 2021 Feb;11(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00460-1.Epub 2020 Nov 10.

Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Cuello-Garcia C, et. al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): Probiotics World Allergy Organ J. 2015; 8(1): 4. Published online 2015 Jan 27. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2

Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, Knot A, Waskiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Olszewską M, Rudnicka L. Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis: An Updated Review. Pathogens. 2020 Jun; 9(6): 463. Published online 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060463

Ojetti V, De Simone C, Sanchez J, Capizzi R, Migneco A, Guerriero C, Cazzato A, Gasbarrini G, Pierluigi A, Gasbarrini A. Malabsorption in psoriatic patients: cause or consequence? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006 Nov;41(11):1267-71.

doi: 10.1080/00365520600633529.

Katta R, Sanchez A, Tantry E. An Anti-Wrinkle Diet: Nutritional Strategies to Combat Oxidation, Inflammation and Glycation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2020 Mar;25(2):3-7.

Lee, D. E. et al. (2015) “Clinical Evidence of Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 on Skin Aging: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study,” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1509.09021

Ramirez J. Guarner F, Fernandez, L, Maruy A, Sdepanian V, Cohen H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 24 November 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.572912

Stubbe C. The Gut Microbiome in Dermatology. Anti-aging Medical News. Spring 2022. p76-80.

Homemade Sauerkraut

Sauerkraut is an amazing two ingredient health elixir. Applying a bit of patience to a mixture of shredded cabbage and salt results in a lactobacillus rich condiment.

Basic Sauerkraut Recipe

Sauerkraut is an amazing two ingredient health elixir. Applying a bit of patience to a mixture of shredded cabbage and salt results in a lactobacillus rich condiment.

Ingredients:

1 medium head organic cabbage, cleaned, quartered and thinly sliced

1-1 1/2 Tablespoon salt per quart of shredded cabbage (I prefer sea salt.)

Directions:

In a large bowl combine the cabbage and salt. Thoroughly mix the ingredients with clean hands until the cabbage has softened and started to release some liquid.

Transfer the mixture to a clean 1 quart mason jar. (I like to use a wide mouth jar.) Pack the mixture into the jar using a spatula, clean hands or a muddler. Tamp the mixture firmly until the liquid released from the cabbage completely covers the mixture.

Apply a weight to the top of the cabbage mixture to keep the cabbage submerged in the brine. A smaller glass jar filled with water (like a 1 cup mason jar), a food safe plastic bag filled with water or a small dish work well.

Cover the jar with a clean dish towel and set it in a dark, cool corner of your kitchen. Check the sauerkraut every few days. If you see scum forming in the jar, remove it and wash the weight before replacing it.

Allow the sauerkraut to ferment between 4-14 days. A longer fermentation time will result in a more "sour" finished product. Taste the mixture periodically. When the mixture has reached the desired tartness, remove the weight, screw a lid on the jar and place the sauerkraut in the refrigerator. Enjoy a forkful daily as a gut supportive treat.

Once you have mastered this simple technique, experiment with adding veggies, herbs or spices to the mixture for additional flavor varieties.

Try some of the other easy ferments:

NATURAL FOODS FOR GUT HEALTH

PRESERVED LEMONS

HOMEMADE COCONUT YOGURT

SHOULD YOU BE TAKING A PROBIOTIC?

Enjoying Bitter Greens: Promote Digestion and Gain Nutrients

As Americans we are sugar-addicted and bitter-phobic, but many cultures embrace bitter flavors. They are packed with vitamins A, C, K and minerals like calcium, potassium and magnesium. They are also great sources of folate and fiber. Adding bitter greens to your diet can be simple. Arugula, endive, broccoli rabe, swiss chard, dandelion greens, escarole, frisée, kale, mizuna, mustard greens, beet greens, radicchio, and watercress can all be found seasonally in the produce section of most local groceries.

Red Belgian Endive

As Americans we are sugar-addicted and bitter-phobic, but many cultures embrace bitter flavors. Europeans have a tradition of “digestive” bitters and the ideal Chinese meal always includes a bitter food on the plate. We humans have taste receptors for five flavors: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and the elusive umami.

These flavors are important and have played a role in our evolutionary development. For example, sweet flavors signify sugars and sources of easy calories. On the other hand, bitter flavors have likely helped us avoid eating toxic substances. Over time we developed tolerance to these flavors, which has allowed us to eat nutritious plants that have bitter-flavors and now they are easily found in your grocery store. The chemical compounds in these plants that are responsible for the bitter flavors have demonstrated beneficial properties, including stimulating appetite, promoting digestive enzyme production necessary for optimal nutrient absorption as well as promoting gastrointestinal motility. Many people already use bitters for this purpose in the form of a morning cup of coffee. In fact, the three most recognized bitters in the American diet include coffee, chocolate and beer.

Kale, Swiss Chard and Arugula

Americans often ignore these wonderfully nutritious bitter greens. They are packed with vitamins A, C, K and minerals like calcium, potassium and magnesium yet low in calories. They are also great sources of folate and fiber. Adding bitter greens to your diet can be simple. Arugula, endive, broccoli rabe, swiss chard, dandelion greens, escarole, frisée, kale, mizuna, mustard greens, beet greens, radicchio, and watercress can all be found seasonally in the produce section of most local groceries. The tender bitter greens can be incorporated into your salad. For the sturdier greens, consider lightly sautéing in a small amount of olive oil with a sprinkle of salt to tame the bitter flavor and make the greens more digestible.

To introduce your palate to these flavors, try the following recipe.

Bitter Greens Salad

Of all the flavors that grace our plate, the bitter flavor is potentially the most fascinating. There is strong tradition around the world to use bitter flavors to help aid digestion, cleanse the body and build vitality. One of the best ways to introduce bitterness to your plate is to incorporate the bitter taste of nutrient dense greens into your salad. Chicory, dandelion, arugula, radicchio, endive or watercress are wonderfully complex tasting greens that are easily found in groceries and farmers’ markets. Slowly increase their proportion to sweeter tasting lettuces in your salad to build up your tolerance.

Author: Erica Leazenby, MD

Serves: 4-6

Time: 10-15 minutes

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

1 teaspoon honey or maple syrup

2 tablespoons olive oil

1/8 teaspoon salt

pepper to taste

6 cups mixed greens like romaine lettuce, endive, radicchio, watercress

Optional add-ins: a thinly sliced apple, fennel or radish

Directions:

Combine vinegar, mustard, honey in a small bowl. Add oils and whisk until well blended. Season vinaigrette to taste with salt and pepper.

Combine greens and any additional toppings in a large bowl and drizzle with dressing. Toss to coat. Serve immediately.

Notes:

Tart, yet sweet apples, like pink ladies or gala apples work well in this recipe. When possible use raw, unpasteurized apple cider vinegar like Braggs brand.

Functional medicine approach to healing autoimmune disease

Autoimmune disease represents an inappropriate immune response. The solution to reaching symptom control and disease remission is supporting the immune system to behave more normally. In conventional medicine, powerful immune modulating drugs are often prescribed. In functional medicine, there is a focus on restoring balance in the body by addressing lifestyle, diet, gut health and nutritional deficiencies among other factors. Conventional and functional approaches are not mutually exclusive and can be used together. The ultimate goal is to lower chronic inflammation that triggers symptoms flare-ups and disease progression.

An autoimmune disease is a condition in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the healthy cells of the body rather than a germ like a bacteria or virus. The type of autoimmune disease is named based on the organ(s) being targeted by the body. Some autoimmune diseases target only one organ. For example, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis involved damage of the thyroid. Other autoimmune diseases, like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), affect the whole body.

Addressing the autoimmune process

Autoimmune disease represents an inappropriate immune response. The solution to reaching symptom control and disease remission is supporting the immune system to behave more normally. In conventional medicine, powerful immune modulating drugs are often prescribed. In functional medicine, there is a focus on restoring balance in the body by addressing lifestyle, diet, gut health and nutritional deficiencies among other factors. Conventional and functional approaches are not mutually exclusive and can be used together. The ultimate goal is to lower chronic inflammation that triggers symptoms flare-ups and disease progression.

It all starts in the gut

About 70 percent1 of the body’s immune system is located in the lining of the gut and is influenced by the health of the gut microbial community2. The immune system here plays a vital role in keeping the body healthy by providing a fine balance between the elimination of invading pathogens and tolerance to healthy self-tissue. Alterations to the gut lining and gut microbial community can cause immune imbalance, leading to autoimmune disorders.

Supporting intestinal health is essential for a healthy immune system and is the ideal place to start a healing journey. The health of the body’s microbiome and gut lining are directly influenced by things like metal health/stress management, diet and sleep3 quality.

Use diet to heal autoimmune disease

Healing the gut with nutrition requires an individualized treatment plan based on what is happening in the gut. A detailed assessment of symptoms combined with specialized testing can provide direction for treatment that may involve correcting microbiome imbalances, parasitic infections or overgrowth patterns.

Nutrition tips to reduce inflammation and help manage autoimmune symptoms

1. Identify your trigger foods.

When the gut lining is unhealthy, people may develop sensitivities to foods. These foods can then perpetuate chronic inflammation. Food trigger will vary person to person and will be different depending on the autoimmune disorder involved. There are certain foods that are common triggers for inflammation and are best avoided with autoimmune disease, such as grains, gluten, dairy, refined and added sugars, alcohol and coffee for a period of time. Once symptoms are improved, these foods are reintroducing slowly back into the diet in a systematic way.

2. Try an autoimmune paleo diet (AIP).

If avoiding top pro-inflammatory foods listed above does not provide relief, then moving to an advanced paleo diet approach may be helpful. An Autoimmune Paleo Diet (AIP) further restricts foods that may be inflammatory including removing all grains, dairy, gluten, legumes, nuts, seeds, nightshade produce, processed foods, and vegetable oils, as well as sugar and sweeteners from your diet to identify foods that may trigger a flare-up. Not everyone needs a diet this restrictive to find relief and healing, but an AIP intervention can be very powerful for healing. An AIP diet can be very restrictive and is not meant for long-term use. The elimination phase of the diet lasts 30 days and is followed by a structured reintroduction phase.

3. Focus on eating a variety of healthy foods.

A common mistake people make when trying to follow an anti-inflammatory diet for autoimmune diseases is restricting the list of foods they eat and eating those same foods over and over again. Focusing eating a variety of foods from the exhaustive list of vegetables, fruits, proteins, etc. that are included in the diet provides healing nutrients like phytonutrients, antioxidants and omega-3’s for healing. Adding a variety of fruits and vegetables into your diet can also help prevent intolerances and ensure you’re getting a spectrum of vitamins and minerals.

4. Address nutrient deficiencies.

Nutritional insufficiencies and deficiencies are common in the US. In people with autoimmune disorders vitamins A and D, omega-3 fatty acids and minerals like zinc and magnesium are especially important for healing. Addressing gut health to optimize nutrient absorption and eating a nutrient dense diet are imperative steps toward healing. Filling up on vitamin A-rich foods, like beef liver and wild Alaskan fermented cod liver oil, and vitamin D-rich foods, such as sardines and salmon can be helpful. For foods that are excellent sources of zinc, go for oysters, beef, crab, turkey, and chicken. And those that are high in magnesium, check out mackerel, spinach, Swiss chard, and avocado. In some cases, adding strategic supplementation to address deficiencies is important. If you have an autoimmune disease, talk to your doctor about regularly checking your levels of these key nutrients.

Addressing autoimmunity requires a personalized approach. Talk with Relish Health to begin your healing journey.

BOOST YOUR IMMUNITY WITH FUNCTIONAL MEDICINE

TESTING, TESTING... WHICH ONES MIGHT BE RIGHT FOR YOU?

References:

1. Vighi G, Marcucci F, Sensi L, Di Cara G, Frati F. Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):3-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03713.x

2. Wu HJ, Wu E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. 2012;3(1):4-14. doi:10.4161/gmic.19320

3. Smith RP, Easson C, Lyle SM, et al. Gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep physiology in humans. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222394. Published 2019 Oct 7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222394

Preserved Lemons

Preserved lemons require only two ingredients, lemon and salt, but together pack a tangy and bright acidic punch for your meal. This secret trick to enhancing salad dressings, dips and marinades is rich in probiotics and vitamin C, both of which can help support your immune system. You can use preserved lemons in any recipe that you would use fresh lemons. Delicious!

Many people are using their quarantine time to create sourdough starters. I've opted for an easier fermentation project. Preserved lemons require only two ingredients, lemon and salt, but together pack a tangy and bright acidic punch for your meal. This secret trick to enhancing salad dressings, dips and marinades is rich in probiotics and vitamin C, both of which can help support your immune system. You can use preserved lemons in any recipe that you would use fresh lemons. Delicious!

🍋🍋🍋

Preserved lemons:

5 organic lemons

2 Tbsp salt

Optional: 1-2 peppercorns and/or a few saffron threads

With clean hands, thinly slice 3 1/2 lemons. Remove the seeds and place them in a clean, small glass jar. Pour the juice of the remaining 1 1/2 lemons over the slices. Add the salt and stir.

Place a smaller glass jar or similar object on top of the lemon slices to keep them submerged in the juice. (I place the lemons in a wide-mouth ball jar and place a smaller juice glass inside.)

Cover the jar(s) with a towel or cheese cloth for protection from dust. Let the jar sit on the counter away from direct sunlight for about 1 week.

After 1 week, refrigerate and use the lemons as desired. Note that a little bit goes a long way.

Is Bone Broth Worth The Hype?

Bone broth is a popular wellness product. The purported health benefits include being a rich source of collagen, amino acids and minerals with anti-inflammatory properties. The nutrients are extracted from the bones through a long cooking process that sometimes includes adding acid (vinegar) to the simmering stock. This is the “recipe” I follow.

Simmering Bone Broth

I’m coming to terms lately that I may have a bit of a hoarding problem in the kitchen. I found no less than 9 quarts of homemade organic bone broth in my freezer. I love squirreling away veggie bits (ends of carrots, leeks, asparagus and onions, squash peels) together with bones from organic chicken. All of these scraps, which are often discarded, make amazing flavored broth that adds extra nourishment in many recipes. In my opinion, broth is what separates the good chefs from the extraordinary chefs. I use this broth in all my soups and often use it as the liquid for cooking rice.

In the world of functional medicine, we LOVE bone broth. It is often cited as a gut-healing food. I frequently recommend its use when I am helping people overcome GI symptoms. It is delicious and well-tolerated, and does seem to anecdotally help people feel better. But, the scientist in me has often wondered if this was just hype or if research has proven this true. Unfortunately, there is very little scientific data about bone broth.

Why drink bone broth?

Bone broth is a popular wellness product. The purported health benefits include being a rich source of collagen, amino acids and minerals with anti-inflammatory properties. The nutrients are extracted from the bones through a long cooking process that sometimes includes adding acid (vinegar) to the simmering stock.

Unfortunately, there is little published research about nutrients in bone broth. Recipes for broth can vary widely adding to the challenges of creating an accurate representation of the liquid. Small studies suggest broth contains modest amounts of chromium, molybdenum, potassium, selenium and magnesium, all of which are essential for health and healing. Other studies, however, suggest that broth contains only a minimal amount of calcium, phosphorus, iron, zinc, and copper. Adding vegetables to the simmering broth does increase the minerals (and the taste) in the finished product. Of note, simmering bones for long periods of time can also extract undesired elements like lead and other heavy metals. Luckily, studies (linked below) suggest that the levels of toxic elements are low and unlikely to be of concern.

How to make your own bone broth

As evidenced by my freezer, I love to make bone broth. Regardless of the lack of scientific data, I continue to see it as a nourishing and delicious component of healthy, flavorful cooking. I feel accomplished when I turn bits of veggies and bone into food that nourishes my family and creates incredible flavor. This is the “recipe” I follow. It is very adaptable to whatever veggies scraps or bones you have on hand. Many people like to purchase beef bones or chicken feet for the sole purpose of making broth. I prefer to use what routinely comes into my kitchen. Since I use the broth in a variety of cooking dishes, I also prefer to not add vinegar to my recipe. I have success creating a rich, gelatinous broth with the recipe below.

Homemade Chicken Bone Broth

Author: Erica Leazenby, MD

Makes: 3 quarts stock

Time: 30 minutes hands-on time (15 minutes prep, 15 minutes packaging)

Ingredients:

1 onion*, halved

1 large carrot* (clean but it does not need to be peeled)

1 celery stalk*

1-2 fennel stalks (optional)

5-10 mushroom stems (optional)

Butternut squash peels (optional)

4-5 whole peppercorns

1 large bay leaf

5-10 parsley stems*

2 sprigs fresh thyme or ¼ tsp dried

1 1x4 inch piece dried kombu** (This seaweed supplies extra minerals like iodine.)

Frame of 1-2 organic or pastured chicken or an equivalent amount of bones, preferably previously roasted

3 quarts filtered water

Directions:

1. Place all ingredients in a slow cooker or pressure cooker.

2. Allow the ingredients to cook for 36 hours in the slow cooker on low heat or 4 hours in the pressure cooker at high pressure.

3. Strain the contents of the broth. Once appropriately cool, place the stock in the refrigerator overnight. The next morning skim off any undesired fat.

4. Pour the stock in 1-quart freezer containers. Store for future use. (I also like to freeze a portion of the broth in 1 cup increments** for convenience.)

* Or use an equivalent amount of scraps. I avoid using cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower or other similar brassica family veggies.

Never fear. If this process sounds overwhelming, studies comparing homemade verses commercially purchased bone broth did not show signifiant difference in nutritional contents.

Culinary primer:

The term broth and stock are often used interchangeably. They are closely related. I have listed definitions below that have been provided by one of my favorite food authorities, Epicurious. What many people term bone broth should technically be called bone stock. I am not sure how bone broth became the popular term, perhaps because it has a better ring to it.

Broth is water simmered with veggies like carrots, celery and onions, aromatic herbs like parsley, bay leaf, thyme and peppercorns and may or may not include meat or bones. It is usually cooked for a short period of time before being strained and seasoned.

Stock is water simmered with veggies and herbs and animal bones (often roasted). It may also include pieces of meat. The water is simmered for longer periods of time before being strained. The goal is to extract the collagen from the connective tissue of the bones so that the stock has a thicker, gelatinous quality.

References:

McCance RA, Sheldon W, Widdowson EM. Bone and vegetable broth. Arch Dis Child. 1934 Aug;9(52):251-8.

Rennard BO, Ertl RF, Gossman GL, Robbins RA, Rennard SI. Chicken soup inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro. Chest. 2000 Oct;118(4):1150-7.

TIME magazine. January 2016. Science Can’t Explain Why Everyone is Drinking Bone Broth. Accessed at: http://time.com/4159156/bone-broth-health-benefits/

Monro JA, Leon R, Puri BK. The risk of lead contamination in bone broth diets. Med Hypotheses. 2013 Apr;80(4):389-90.

Hsu DJ, Lee CW, Tsai WC, Chien YC. Essential and toxic metals in animal bone broths. Food Nutr Res. 2017 Jul 18;61(1):1347478.

Dr. Kara Fitzgerald Bone Broth White paper: https://gallery.mailchimp.com/36f67b141008ab16392748797/files/76dd7b45-a07a-4c41-bc8d-fd4a497e1710/2019_Bone_Broth_Report_2_.pdf?mc_cid=d7e7a163d7&mc_eid=f46483d568

Broth vs Stock https://www.epicurious.com/ingredients/difference-stock-broth-bone-broth-article

Alcock RD, Shaw GC, Burke LM. Bone Broth Unlikely to Provide Reliable Concentrations of Collagen Precursors Compared With Supplemental Sources of Collagen Used in Collagen Research. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019 May 1;29(3):265-272. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0139. Epub 2018 Sep 26.

** Amazon affiliate link

Is your bloating caused by SIBO?

You have probably heard that we are what we eat. I believe we are more accurately “what we absorb.” Much of our health and wellbeing hinges on a well-functioning gastrointestinal tract to absorb the nutrients that support the rest of the body. Pesky symptoms like constipation, diarrhea or frequent bloating and gas suggest that the GI tract may be compromised. These symptoms can be associated with small intestinal bowel overgrowth.

You have probably heard that we are what we eat. I believe we are more accurately “what we absorb.” Much of our health and wellbeing hinges on a well-functioning gastrointestinal tract to absorb the nutrients that support the rest of the body. Pesky symptoms like constipation, diarrhea or frequent bloating and gas suggest that the GI tract may be compromised. These symptoms can be associated with small intestinal bowel overgrowth.

What is Small Intestinal Bowel Overgrowth (SIBO)?

Before we look at how the bowels can become overgrown with organisms, it is important to understand how the digestive system works. The intestines are comprised of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestines (also called the colon). Gastric acid produced in the stomach initiates the digestive process but also acts to suppresses the growth of ingested bacteria and control bacterial counts in the upper small intestines. The small intestines are where the majority of food is digested, and nutrients absorbed. The small intestines have an impressive length of approximately 10-15’ and are home to a large network of immune cells that help fight infection and regulate our immune system. The small intestines have a normal muscular activity which creates waves that move the intestinal contents, like food, through the gut. Our entire digestive tract is populated with trillions of organisms that make up our microbiome. The bulk of these bacteria live in our large intestines. The small intestines have relatively few bacteria in comparison to the large intestine. The normal (beneficial) bacteria are an essential part of the healthy small bowel. They help protect against bad (i.e. pathogenic) bacteria and yeast that are ingested. They also help the body absorb nutrients, and produce several vitamins like folate and vitamin K. Any disruption in the quantity of organisms, or balance of species, in the microbiome can be diagnosed as SIBO.

What causes SIBO?

An overgrowth of organisms in the microbiome can occur when the stomach has inadequate gastric acid or the motility of the small intestines is slow. Food that nourishes us also feeds the microbiome and is subject to fermentation in the small intestines, especially if it spends prolonged time in the small intestines. This fermentation can produce gas (hydrogen or methane) that can be felt as bloating, belching, flatulence, reflux or the gas can trigger symptoms such as diarrhea or constipation.

The conditions below are risk factors for SIBO and slow motility:

Anatomic changes due to surgeries, scaring or small intestine diverticula

Slow motility due to gastroparesis, celiac disease, scleroderma or pseudo-obstruction

Metabolic changes such as those associated with diabetes or low gastric acid

Advanced age

Organ dysfunction like kidney failure, pancreatitis or liver failure

Frequent medications use with antibiotics or gastric acid suppressers

How do you test for SIBO?

SIBO is most often diagnosed with a breath test. The test measures how much hydrogen or methane gas are in your breath. Both gasses are a byproducts of bacteria breaking down sugar in your gut. There are no blood or stool tests for SIBO. However, anemia, low B12 levels and markers of malabsorption may be seen on blood testing.

How do you treat SIBO?

SIBO treatment includes 4 goals:

Correct the cause: SIBO is notoriously challenging to treat with a high recurrence rate. If possible, identifying and resolving the condition that initially predisposed one to the overgrowth increases the success rate of treatment.

Provide nutritional support: Adopting a nutrient dense diet, supporting digestion/absorption and occasionally using targeted supplements can support gut healing. There are multiple dietary approaches for SIBO that also help relieve symptoms.

Treat the overgrowth: Although some antibiotics can predispose users to SIBO, there are other specific antibiotics and anti-microbial herbs that are useful in treating the overgrowth.

Prevent relapse: Sometimes it is difficult to completely resolve the predisposing risk(s) for SIBO. Using targeted pro-kinetics supplements of medications to promote small bowel motility can help prevent SIBO recurrence.

Need help treating bloating, gas or abnormal stool patterns? Relish Health is here to help.

Learn more about optimizing your gut health:

7 Steps to Fight Reflux and Bloating

Promote Digestion and Gain Nutrients with Delicious Bitter Greens

Advice for Staying Regular When You Travel

Is a Low FODMAP diet right for you?

References:

Collins JT, Nguyen A, Badireddy M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Small Intestine. [Updated 2020 Apr 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459366/

Dukowicz AC, Lacy, BE and Levine, GM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Comprehensive Review Gastroenterology & Hepatology Volume 3, Issue 2 February 2007 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3099351/pdf/GH-03-112.pdf

Bures J, Cyrany J, Kohoutova D, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(24):2978‐2990. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

Natural Foods for Gut Health

Fermented foods have been a part of cultures for thousands of years. Historically, fermentation was a way to preserve food, but as we are now learning, it is also a way to ensure a healthy microbiome. Fermented foods include live cultures that make them natural probiotics and aid our digestive and immune systems. Modern practices like refrigeration and pasteurization have made these traditional foods less common in our culture today. Reintroducing these delicious and natural solutions can help give your gut a health boost.

It is true that we are what we eat, but it is more accurate to say that we are what we absorb. Our overall health is intimately tied to the health of our digestive system. Our digestive system is a complex organ that contains trillions of bacteria. This bacterial community, called the microbiome, is responsible for helping absorb our nutrients, manufacture some of our vitamins and help regulate our immune system. Keeping this bacterial community happy, healthy and diverse is vitally important for ensuring proper absorption and optimal health.

Fermented foods have been a part of cultures for thousands of years. Historically, fermentation was a way to preserve food, but as we are now learning, it is also a way to ensure a healthy microbiome. Fermented foods include live cultures that make them natural probiotics and aid our digestive and immune systems. Modern practices like refrigeration and pasteurization have made these traditional foods less common in our culture today. Reintroducing these delicious and natural solutions can help give your gut a health boost.

Try some of these favorites:

1. Kefir is a fermented dairy drink similar to yogurt. The term originated in Russia and Turkey and is translated to mean “feels good.” It has a mildly acidic, tart flavor and contains many more strains as well as higher levels of beneficial bacteria than standard yogurt. When purchasing, choose kefir with minimal amounts of added sugar. Enjoy as a drink, in a smoothie, or with granola.

2. Sauerkraut is made from fermented cabbage and other vegetables. Artisanal varieties are often flavored with beets, apples or carrots. Sauerkraut is fermented by wild strains of the beneficial bacteria, lactobacillus. It has a pleasant sour flavor that is excellent as a condiment for entrées, salads and savory toasts. When purchasing, be sure to find the product in the refrigerated section of the grocery. (The other version on the aisle shelves has been pasteurized and no longer contains the desired beneficial bacteria.) Sauerkraut can be made easily at home.

3. Kimchi is similar to sauerkraut, but is often made with napa cabbage and radishes. It is Korean in origin and is often spicy.

4. Kombucha is made from fermented sweet tea and is thought to originate from Japan. Kombucha is made by adding a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) into tea and allowing the tea to ferment for a few days to a week. The resulting product is effervescent and has a tangy flavor.

5. Coconut kefir is made by fermenting the water of young coconuts in a similar manner to making dairy kefir. It is not as high in probiotics as its dairy cousin, but it is very refreshing.

6. Yogurt can be an excellent probiotic food, but only if chosen wisely. Many commercially available yogurts can contain high amounts of added sugar and dyes. The quality of dairy is important to consider.

7. Raw apple cider vinegar contains the acetobacter that is responsible for making the acetic acid that gives vinegar its characteristic flavor. Research has demonstrated that apple cider vinegar can help control blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar. Enjoy raw apple cider vinegar in salad dressings or as a diluted beverage.

8. Miso is a traditional Japanese product. It is created by fermenting soy beans or chickpeas with a yeast called koji. Miso can be made into a soup but is also delicious enjoyed as a condiment in salad dressings, sauces or marinades.

9. Pickles made by fermenting cucumbers with salt and water are also a source of beneficial lactobacillus. They are low in calories, but eat in moderation as they may contain a fair amount of salt. Make them at home or find in a specialty grocery in the refrigerated section. (The other pickles located in the aisle shelves are made with vinegar and do not contain the necessary live cultures.)

Promote Digestion and Gain Nutrients with Delicious Bitter Greens

As Americans we are sugar-addicted and bitter-phobic, but many cultures embrace bitter flavors. They are packed with vitamins A, C, K and minerals like calcium, potassium and magnesium. They are also great sources of folate and fiber. Adding bitter greens to your diet can be simple. Arugula, endive, broccoli rabe, swiss chard, dandelion greens, escarole, frisée, kale, mizuna, mustard greens, beet greens, radicchio, and watercress can all be found seasonally in the produce section of most local groceries.

Bitter green salad

As Americans we are sugar-addicted and bitter-phobic, but many cultures embrace bitter flavors. Europeans have a tradition of “digestive” bitters and the ideal Chinese meal always includes a bitter food on the plate. We humans have taste receptors for five flavors: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and the elusive umami.

These flavors are important and have played a role in our evolutionary development. For example, sweet flavors signify sugars and sources of easy calories. On the other hand, bitter flavors have likely helped us avoid eating toxic substances. Over time we developed tolerance to these flavors, which has allowed us to eat nutritious plants that have bitter-flavors and now they are easily found in your grocery store. The chemical compounds in these plants that are responsible for the bitter flavors have demonstrated beneficial properties, including stimulating appetite, promoting digestive enzyme production necessary for optimal nutrient absorption as well as promoting gastrointestinal motility. Many people already use bitters for this purpose in the form of a morning cup of coffee. In fact, the three most recognized bitters in the American diet include coffee, chocolate and beer.

Americans often ignore these wonderfully nutritious bitter greens. They are packed with vitamins A, C, K and minerals like calcium, potassium and magnesium. They are also great sources of folate and fiber. Adding bitter greens to your diet can be simple. Arugula, endive, broccoli rabe, swiss chard, dandelion greens, escarole, frisée, kale, mizuna, mustard greens, beet greens, radicchio, and watercress can all be found seasonally in the produce section of most local groceries. The more tender greens can be incorporated into your salad. For the sturdier greens, consider lightly sautéing in a small amount of olive oil with a sprinkle of salt to tame the bitter flavor and make the greens more digestible.

To introduce your palate to these flavors, try the following recipe.

Bitter Greens Salad

Of all the flavors that grace our plate, the bitter flavor is potentially the most fascinating. There is strong tradition around the world to use bitter flavors to help aid digestion, cleanse the body and build vitality. One of the best ways to introduce bitterness to your plate is to incorporate the bitter taste of nutrient dense greens into your salad. Chicory, dandelion, arugula, radicchio, endive or watercress are wonderfully complex tasting greens that are easily found in groceries and farmers’ markets. Slowly increase their proportion to sweeter tasting lettuces in your salad to build up your tolerance.

Author: Erica Leazenby, MD

Serves: 4-6

Time: 10-15 minutes

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

1 teaspoon honey or maple syrup

2 tablespoons olive oil

1/8 teaspoon salt

pepper to taste

6 cups mixed greens like romaine lettuce, endive, radicchio, watercress

Optional add-ins: a thinly sliced apple, fennel or radish

Directions:

· Combine vinegar, mustard, honey in a small bowl. Add oils and whisk until well blended. Season vinaigrette to taste with salt and pepper.

· Combine greens and any additional toppings in a large bowl and drizzle with dressing. Toss to coat. Serve immediately.

Notes:

Tart, yet sweet apples, like pink ladies or gala apples work well in this recipe. When possible use raw, unpasteurized apple cider vinegar like Braggs brand.

7 Steps to Fight Reflux and Bloating

Reflux and bloating are common complaints that I hear frequently in the office. If you struggle with these symptoms as well, know you are not alone. It is estimated that 44% of Americans have heartburn once a month and as many as 10 million people have daily symptoms.

Food is medicine and can be part of the trigger or the healing of these common complaints.

Listed below are seven steps that may help you identify and address potential triggers for reflux and bloating.

Reflux and bloating are common complaints that I hear frequently in the office. If you struggle with these symptoms as well, know you are not alone. It is estimated that 44% of Americans have heartburn once a month and as many as 10 million people have daily symptoms.

Food is medicine and can be part of the trigger or the healing of these common complaints. Food plays many roles in our lives. It is delicious, comforting and linked to our identity and social connectedness, but is also the fuel and building blocks for health. It is information for your cells and gene expression. You eat approximately one ton of food each year and can change your body chemistry every time you eat.

Listed below are seven steps that may help you identify and address potential triggers for reflux and bloating. At a recent workshop event, we discussed these in more detail and sampled foods that can aid digestion. Look for future sessions like this on the Event page.

1: Eat mindfully at the table (and your desk and steering wheel are not tables). Mindfulness can promote the parasympathetic nervous system responsible for the “rest and digest” function of the body. Eating slowly and paying attention to your food and how your body is responding can improve your overall digestion.

2: Get your digestive juices going. Bitter flavors can promote digestive juices. Consider adding bitter greens (eg. arugula, endive, radicchio, mustard greens, chard, parsley, cilantro, broccoli rabe or vinegars, etc.) to your plate.

3: Tend your inner garden. Our gut is home to a host of bacteria. Add fermented foods or probiotics to your diet to encouraged friendly flora. Make sauerkraut, kimchi, sour pickles and/or kefir regular condiments on your plate. Consume adequate fiber to keep the good bacteria happy and thriving and avoid processed, refined foods.

4: Some foods can actually aid digestion. Consider adding ginger, fennel seeds and bitter flavors to your diet. Be aware of foods that may trigger reflux symptoms. They may include: fried and fatty foods, spicy foods, citrus, tomato-based foods, processed foods, alcohol, caffeine and tobacco.

5: Consider eliminating and re-introducing foods that commonly trigger sensitivities. Start with eliminating gluten and dairy for 2-4 weeks then reintroducing and monitoring for symptoms. If bloating is still an issue, there are other diets to consider that are known to improve symptoms, including the FODMAP diet.

6: Stay active and get your beauty rest. Movement promotes gastrointestinal motility and helps maintain ideal weight while sleep is important for overall health. Avoid going to bed with a full stomach by eating at least 2-3 hours prior to going to bed. Elevate the head of the bed to minimized night time reflux.

7: Seek help. While these interventions are generally safe for everyone, frequent or daily gastroentestinal symptoms, weight loss, blood in your stool, black tarry stools or a family history of gastrointestinal problems may siginfy more significant problems and need to be further evaluated. If you need more help identifying your particular triggers, come see me at Relish Health and we'll work on an individual treatment program designed for you.